The Question:

Is DNA evidence reliable enough?

Download Forensic Science Debate Kit

Erin Nevin - Juror - For

I just received a letter asking me to do jury service. It’s very annoying to have to take time off work right now, and what could I contribute?

DNA evidence is objective and almost foolproof; it should be used to say whether someone is guilty or not; it shouldn’t be left to the opinions of jurors! What if my fellow jurors just don’t like the accused person, perhaps because of social prejudices or because they don’t seem scared enough – they could wrongfully convict or acquit. What if we are emotionally led by clever lawyers? It makes me uneasy.

Fact: Decision-making research shows that we tend to make decisions based on our emotions and then justify them afterwards.

Issue: The impact of emotions depends on who has those emotions: jurors find angry men convincing, and angry women unconvincing!

Question: Should emotion figure in a juror’s decision – or is it always wrong?

Daiyu Hu - Defence Lawyer - Against

As a defence lawyer, it’s my job to remind people to ask questions. If your DNA is found at a scene, how did it get there? Did you put it there, or did somebody else?

Scientists have such powerful technologies, they can now analyse trace DNA – tiny fragments passed by touching. But maybe if I shake your hand, then touch a knife, and later someone else uses it, your DNA could be at a crime scene. It’s important to remind people of that. Of all the possibilities.

Fact: DNA analysis is now so sensitive that the amount found in 76 cells is enough to make a profile… but too little to detect what biological material it’s from, e.g. skin, blood, or semen.

Issue: Just because trace DNA is found on an object, doesn’t necessarily mean the person it is from ever touched it, but juries tend to assume they did.

Question: Why do forensic scientists care what biological material DNA comes from – would it change the forensic implications?

Panaya Rai Scene of Crime Officer - For

We perform checks and take control samples to make sure the DNA we get from crime scenes isn’t contaminated. Our own DNA gets taken and excluded from samples.

We not only wear the full body suit, we have to take pictures, bag everything, document everything, measure the distances between items. We have precise procedures. This is all to preserve the quality of the evidence. Yeah sure, it’s possible to contaminate DNA, but we make sure that doesn’t happen at a crime scene.

Fact: SOCOs have been involved in British policework since 1968. They do not investigate crimes or analyse evidence; their job is retrieving high quality evidence from crime scenes.

Issue: DNA is invisible to the human eye. SOCOs use professional judgement and years of experience to identify where DNA samples may be found at a crime scene.

Question: Is it better to take lots of samples which will take time to process, delaying an investigation, or fewer and risk missing something?

Graham Ross Medical Statistician - Against

Medical statisticians like me calculate a match probability between a DNA sample and a suspect. We don’t say the DNA definitely belongs to them, we give a chance.

It has to be only a chance: analysts don’t sequence everything. There are millions of base pairs in a DNA sample and it’s time consuming to sequence, so we take bits called short tandem repeats (STRs). The more you sequence, the less likely you’ll find two matches. We use computer software to make estimates and different software gives different results.

Fact: If the probability that someone other than the suspect is the source of crime scene DNA is less than 1 in 1 billion, we still say 1 in 1 billion so that juries don’t have to grapple with absurdly small numbers.

Issue: Analysis of complex DNA cannot be entirely objective: when the match isn’t quite right, scientists have to make a decision: is it a poor match or a non-match?

Question: The genome holds lots of information about an individual. Why are some people reassured that scientists sequence only PART of a genome?

Jake Okiro - 16y/o - For

I don’t trust the police. People who are ethnically minoritised or from poorer backgrounds get accused and arrested and convicted more than other people.

DNA is an great, unbiased tool for showing the truth. The police can’t stitch up the genome to make it black, or match whoever they grab for it. It isn’t even the same person who interprets the DNA as collects it – not like you see on TV. The person who tests it probably doesn’t know if it belongs to a suspect or a victim.

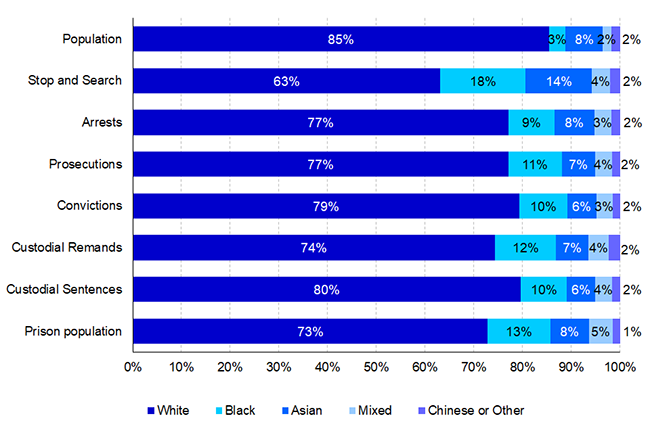

Fact: In the UK in 2020, black people made up 13% of the prison population, but only 3% of the general population.

Issue: DNA can’t identify a biological human race – races are social not biological, and usually come from appearance, culture, or family history. We inherit 50% of our DNA from each parent randomly, so you could even have a direct relative but share no DNA.

Question: Are the police responsible for ethnic differences in arrests and convictions, or does this reflect wider societal issues, such as poverty?

Saïd Ali - 20y/o identical twin - Against

I’m an identical twin, but we’re very different people. It worries me that my twin committed a crime once, and his DNA was taken. Now the police have that information on me, because our DNA is basically the same.

They can keep it in the national database forever and I could be falsely accused of a crime. That scares me. I’ve read that there are other kinds of forensic evidence that could tell us apart, like fingerprints and vein patterns on the back of your hands, but not DNA. It’s definitely not a gold standard.

Fact: Fingerprints and vein patterns develop in the womb and are affected by small changes in womb fluid, foetal position and movement, and so are not identical for identical twins.

Issue: When analysts choose a bit of DNA to sequence, it is pot luck whether this contains a mutation that would distinguish between twins.

Question: Is the National DNA Database ethical? Is it okay to store information on it from people who have not committed crimes?

Will Tenor - Psychologist - For

DNA evidence is reliable, matching a crime scene sample to a suspect correctly almost every time. But people don’t want to hear about it if there’s a witness or a confession.

But these aren’t reliable enough: witnesses can make mistakes, have false memories, and vulnerable people get pressured into false confessions. The burden of proof should be really high because it can have huge psychological implications on someone to be wrongfully convicted and prevent them from getting a job, maintaining relationships, or seeing their children grow up.

Fact: By law, under 18s must have an appropriate adult with them when interrogated by the UK police, as a safeguard against pressures that lead to false confessions.

Issue: DNA evidence has proved that some confessions to crimes are false.

Question: Is the risk of wrongful conviction ever worth taking? How often do you think witnesses and confessions are wrong?

Eira Hughes - Fingerprint expert - Against

Fingerprints have falsely convicted people. We used to say if there were twelve points the same, the fingerprints matched.

But since the Shirley McKie case, twelve points of difference are used: excluding people. This leaves multiple suspects, but isn’t proof of guilt. DNA is no different. One day we’ll probably find a better way to interpret it. There is no gold standard: scientific evidence is strongest when there is complementary evidence – several techniques used together and pointing at the same person.

Fact: No two identical fingerprints have ever been found, including on different fingers of the same person.

Issue: Fingerprint evidence has led to false convictions, for example, police officer Shirley McKie, who was accused of lying under oath when her fingerprint was matched (incorrectly) to some found at a crime scene she’d never visited!

Question: Fingerprinting is a different scientific process to DNA analysis – can its history and findings truly reflect the strengths and weaknesses of DNA?

Additional Resources

SCROLL DOWN FOR THE EXTERNAL RESOURCES

⚠️ Some of this subject matter may be challenging for some audiences. ⚠️

National statistics – Ethnicity and the Criminal Justice System

This graph was produced by National statistics in 2020 as part of a study on ethnicity and the Criminal Justice System (CJS).

“Outcomes for minority ethnic children are often more pronounced than White children at various points of the CJS. Differences in outcomes between ethnic groups over time present a mixed picture, with disparity decreasing in some areas and widening in others.”

How Long can the Police Keep my DNA and Fingerprints?

If you have been arrested for a recordable offence, then the police will have the right to take a DNA sample and fingerprints.

The police can retain your DNA and fingerprints in certain circumstances, but there a number of situations where the police must delete your DNA and fingerprints.

Watch the full video on YouTube here.

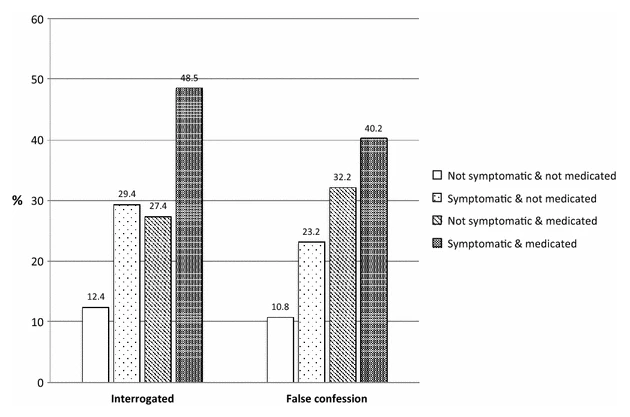

A study to look at police arrest and false confessions in connection to severity of the ADHD condition/symptoms.

A national epidemiological study investigating risk factors for police interrogation and false confession among juveniles and young persons.

Over a study with 22,226 young persons in two age groups; 14–16 and 17–24 years. The older group was significantly more likely to have been interrogated by the police but the younger group were much more vulnerable to false confession during interrogation.

False Confessions: Causes, Consequences, and Implications for Reform

The psychology of interrogation reveals police techniques that can lead innocent people to confess, often producing wrongful convictions.

In recent years, DNA exoneration cases have shed light on the problem of false confessions and the wrongful convictions that result.